In a Bloomsbury bookshop last October, two days after the death of a close friend, I found myself in the store’s horror section. On a whim I bought a collection of disturbing short stories by Robert Aickman called Compulsory Games. Only on the train home did it occur to me that choosing to read horror fiction in a moment of bereavement was a bit odd. Nevertheless Aickman’s ‘strange stories’ (I went on to read four volumes of them) sparked a concerted foray into horror and a dozen or so writers — from E Nesbit to H.P. Lovecraft, Shirley Jackson to William Peter Blatty, Grady Hendrix to Thomas Ligotti and many more. These are some findings from the weird world of horror.

Glimpsing larger worlds

I want to draw a parallel, briefly, with poetry. I respond to poems that slap you in the face like a Zen monk. I love how a line or image can jolt you to a realisation that the world is more beautiful, moving and — this is my point — far larger than before.

It may be why people with little interest in poetry will still resort to it at weddings, funerals or moments of heartbreak. Poetry provides a path away from the hard realities of life by changing our perspective. Take W.H. Auden’s Funeral Blues. The poet asks us, in the rhetoric of grief, to ‘Stop all the clocks’ — not just one clock, but all the clocks in the world. Later, the poem says, ‘He was my North, my South, my East and West’. This is personal grief stretched to wrap around the whole world. In my own moment of bereavement, horror did the same job for me. Why was that?

For a horror story to work, it must also allow you a glimpse of something far larger than yourself. If poetry can show us the sublime, horror can shrink us until we feel powerless in the face of vast, unknowable forces. For the readers of both poetry and horror, however, result is the same. The world has become larger and less stiflingly mundane. Horrorstör (2014) by Grady Hendrix, is a good example of this, set in an Ikea-like store whose doors open into a horrific supernatural prison and its terrifying denizens. It’s funny too.

Three entrances into hell

The oldest and strongest emotion of mankind is fear, and the oldest and strongest kind of fear is fear of the unknown.

H.P. Lovecraft

The opening sentence of H.P. Lovecraft’s landmark essay Supernatural Horror in Literature (1927) is hard to take issue with. But I also think that there are familiar entrances into this huge realm of the unknown.

1. The Door of Religion

The Case Against Satan (1962) by Ray Russell and, more famously, The Exorcist (1971) by William Peter Blatty both use religious ideas of God and the Devil, to create a vast, menacing backdrop to the action. The plots have strong similarities, in both stories young girls channels wild and hellish forces. These must be tackled by men of wavering faith, who are forced to abandon their rational and scientific impulses in the face of demonic possession.

The famous movie version of The Exorcist (1973) may have influenced the real life case of Anneliese Michel. Annaliese appeared not to respond to psychiatric treatment, and sadly died of thirst and starvation while in the care of her family and two Roman Catholic priests. These priests were later found guilty of negligent homicide.

Another story drawing its horrific heft from religion is Ira Levin’s Rosemary’s Baby (1968) where a woman, under the evil influences, becomes pregnant with the Antichrist, the child of Satan.

You only have to think of the work of poets like Milton or Dante to realise religion and horror are centuries-old bedfellows. ‘I came to myself in a dark wood where the straight way was lost’, writes Dante. To escape this entanglement, he needed to progress through the vastnesses of hell and purgatory.

2. The Door of Mythos

H.P. Lovecraft has a towering influence in horror circles. Despite a teenage phase immersed in the stories of his friend and devotee Clark Ashton Smith, I had read very few of his stories until recently. He is a master of horror. He is also a vile racist, even for someone publishing in the 1920s and 30s. He portrays black and biracial people as horrific barely human entities. If you are able to hold your nose enough to overlook this you will discover why his influence is so great. His tactic for bringing supernatural horror to his readers is the invention of a mythology about a monstrous race from the stars, who lived before humans and will persist beyond them. The tentacle-faced Cthulhu (see above) is the greatest of these.

I am hard pressed to understand why The Cthulhu Mythos has become so influential, to the extent that it has become a shared fictional universe used by other writers — in what must have been an early form of fan fiction.

The beginning of the seminal story, The Call of Cthulhu, shows how Lovecraft engineers an immense backdrop, against which the plot about the discovery of clues to an unknown and monstrous race can unfurl.

We live on a placid island of ignorance in the midst of black seas of infinity, and it was not meant that we should voyage far. The sciences, each straining in its own direction, have hitherto harmed us little; but some day the piecing together of dissociated knowledge will open up such terrifying vistas of reality, and of our frightful position therein, that we shall either go mad from the revelation or flee from the deadly light into the peace and safety of a new dark age.

H.P. Lovecraft, The Call of Cthulhu (1926)

I would also argue here that J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings certainly contains elements of horror and, like Lovecraft, this is rooted in an even richer mythos.

3. The Door of Disillusionment

During my new horror craze, I have become a fan of Thomas Ligotti (b.1953). While I find his prose sometimes heavy going, when his stories are good, they are magnificent. His work has already found its way into Penguin Classic status, collecting the stories of Songs of a Dead Dreamer and Grimscribe in one Penguin volume. Lovecraft’s influence is here, and one of Ligotti’s most famous stories, the Last Feast of Harlequin, is dedicated to Lovecraft’s memory.

Ligotti’s work often derives its power from the conceit that the world is absolutely horrific, and it is only through the collective madness of optimism, that we fail to see the world for what it truly is: huge and terrifying.

An a wonderful Ligotti story, In The Shadow of Another World, the protagonist gains entry to a tower whose windows enable the scale and weirdness of reality to be properly seen.

‘For the visions they offered were indeed those of a haunted world, a multi-faceted mural portraying the marriage of insanity and metaphysics… After my eyes closed, shutting out the visions for a moment… It was then I realised that this house was possibly the only place on earth, perhaps in the entire universe, that had been cured of the plague of phantoms that raged everywhere.’

Thomas Ligotti, In the Shadow of Another World (1991)

This is an act of disillusionment, of the stripping away of illusion to see the vast, terrifying truth behind it.

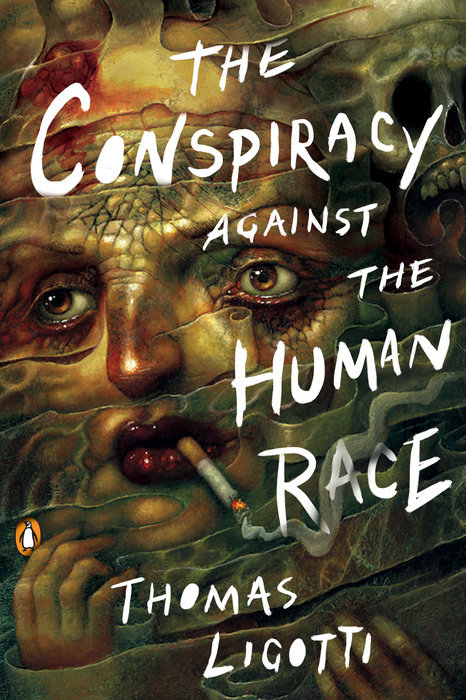

Ligotti’s pessimism is condensed in a fascinating non-fiction book called The Conspiracy Against the Human Race. It is an idiosyncratic survey of pessimism, and is peppered with grim insights, such as this cheery reflection on the moment of death.

‘And for the first time you feel that which you have never felt before—the imminence of your own death. There is no possibility of self-deception now. The paradox that came with consciousness is done with. Only horror is left. This is what is real. This is the only thing that was ever real, however unreal it may have seemed.’

Thomas Ligotti, The Conspiracy Against the Human Race (2010)

Ligotti’s handling of this vast reality belittles us into the weird pleasure of fear.

And for me, the penny drops

In my bout of supernatural horror, I realised something that had been staring at me like a creepy marionette half my life. There is a horror in a good deal of my own work. I called my second poetry pamphlet ‘The Nightwork’, I have written poems about monsters, and doubles, and psychological horror. All my plays are comedies, but three of them have a horrific backdrop. My short stories often have been explicitly horror or weird fiction. But only now has the penny dropped.

Poetry can accommodate horror and sublime moments, and horror can do that too. Also horror can reassure you that your life is better than, say, going mad with alcoholism and trying to kill your family as in Stephen King’s The Shining, or turning into a bestial murderer, as in Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. Ultimately, it is not this reassurance I seek. I thrill to horror’s moments of dark and expanding wonder.

And as I detail here, this new horror craze led me to sending a story, to Matthew Rees at Horla who was kind enough to publish it. I find myself in a new phase of explicitly writing horror, and I find I am loving it.

I think I’ll leave the last word to a poet. Here’s Rilke, from the first of The Duino Elegies (as translated by J. B. Leishman and Stephen Spender).

For Beauty’s nothing / but the beginning of Terror we’re still just able to bear, / and why we adore it so is because it serenely / disdains to destroy us.

Raine Maria Rilke, The Duino Elegies (1929)

Leave a comment